[ 6 ]

Using Character Development in Product Design

Reluctance to Use Personas

Over my years working as a UX designer, I’ve seen a reluctance to create user personas, and more specifically, detailed personas. I’ve met this reluctance in the teams and companies where I’ve worked, with people that I’ve mentored and coached, and have come across it in articles and in social media posts. Many of you who read this book will probably be skeptical of personas, too. Part of this skepticism comes down to how they’re used, or rather not used, on projects, but part of it is also due to a common belief that the team knows who their audience is, so there is no need to articulate it. There are better and more important things to get on with, like an actual solution or creative idea.

I write this with no judgment because I get it. Sometimes the audience feels so obvious that the need to spend time on personas is lower, all things considered, than “doing the actual work.” However, doing the actual work is dependent on knowing who that work is for and why. Freelance UX researcher Meg Dickey-Kurdziolek writes, “Being a user-centered designer means that you deliberately seek out the stories, data, and rationale behind your users’ motivations.”1 Many organizations believe that they have a good understanding of their users and customers, there are some big surprises usually arise when you do more detailed research into who they actually are and go beyond the stereotypes. Assumptions often lead us in the wrong direction, or if we don’t look into the data, we might miss a key part of the audience. One big department store, for example, realized only after looking into its data that although women represented the largest volume of sales, it was actually men who drove the most value.2

Now, breaking down our audience into larger segments like “men” and “women” doesn’t do us enough good when it comes to shedding light on the needs of both current and potential users and customers. In marketing, we’re increasingly moving away from demographic-based segmentation and turning traditional classification on its head. Instead, we’re starting to turn to data and the networks of consumers who are similar to each other, not forming stereotypes like we’re used to, but archetypes that are based on data and insight. This type of segmentation provides far more value and a more accurate picture of the people our products and services are intended for than any broad classification like “millennials,” “mums,” or “entrepreneurs.”

As the story about the user who was going to buy a dog in the preceding chapter started to tell us, no user’s story is the same. The use case, or Jobs To Be Done (JTBD), might be the same—research and buy a dog—but everything else that goes into making that story come to life will, with 100% certainty, be different for every single user. No matter how simple and generalized we want to keep things, people aren’t simple or general.

The things we need to do and the reasons we use websites, apps, and other products and services aren’t simple either. We’re increasingly talking about end-to-end experiences and about CX. To ensure that we can provide value and help users throughout their “end-to-end” experience, we need to understand all the moments that go into it—all the different touch points and what will influence each moment and determine the outcome of the next.

Users bring not only varying existing knowledge into an experience, but also different past experiences. With two first-time visitors, one might have no previous knowledge or experience, and one might have a wealth of previous knowledge and experience from, for example, other similar sites. The former will need more hand-holding and background information, whereas the latter might prefer a “straight-to-what-I’m-looking-for” kind of experience. The opposite, with regard to background knowledge, can also apply to your returning users, with the gist of it all being that every user goes on their journey. Rather than making broad statements and decisions about what users as a group want, we should acknowledge that factors like prior knowledge, backstory, and mindset also play a role in a user’s experience and expectation alongside the other factors that we hopefully define.

Chuck Sambuchino, a freelance editor and former editor with Writer’s Digest Books, offers a really nice metaphor for developing characters. He remembers when cameras had something inside of them called film, and that in order to get the pictures off the film, a technician had to treat it with some chemicals inside a “mysterious darkened room,” and as if by magic, the image would appear on the special paper. But, if the process didn’t go as planned, you could end up with fuzzy or dark or overexposed images. The key to getting a clear photograph depended largely on how the technician developed the film. “If we want readers to have a vibrant mental image of our characters, we have to spend some time in the dark room,” Sambuchino explains.3 The same goes for doing research into our users and what matters to them in the multidevice experiences that we design: “If you don’t understand your users, you will never build great products.”4

The Role of Characters and Character Development in Storytelling

In Aristotle’s seven golden rules of storytelling, the plot and the characters are on par with each other in terms of their importance to the story. Without compelling characters, there won’t be any story to speak of. It’s the characters that we follow throughout the story, the ups and downs that they go through. We follow their personal development, the people they meet and fight along the way, and the lessons they learn. We cheer for them from the moment the dramatic question is asked to the moment it’s answered. It’s them we invest in emotionally, and why we care so much that we keep watching or turning the page until we find out how the story will end.

It’s not a given, however, that we will care about the characters in the stories that we watch or read. Some characters we don’t like because of the actors who play them, and other times we simply don’t connect with them.

For the writer or creator, this is, of course, not ideal. Even if we don’t think about it, a relationship is created with the audience in every story we’re telling, or at least that’s what we’re hoping to do.5 The surest way to do that is through the emotions of the characters that the story is about. Martha Alderson of The Writer Store, an online resource for writing and filmmaking tools, tells us, “Thoughts can lie. Dialogue can lie, too. However, emotions are universal, relatable and humanizing. Emotions always tell the truth.”6

While it’s the character’s motivations that fuel the story and propel it forward, John Truby, a screenwriter, director, and screenwriting teacher, argues that in some instances, particularly for superhero stories, what makes us care about the character is their weakness. According to Truby, what we as an audience want to find out most is not whether the character accomplishes their goal, but whether they overcome their weakness.7 This weakness can be closely linked to the protagonist’s goal and motivations, but also to their emotions and the challenges they faced in overcoming that weakness.

This journey to accomplish their goals must affect the character emotionally. Only then do we connect. This goes for all the characters in the story, not just our main protagonist. The change that the character goes through is often referred to as the character arc, which Wikipedia describes as “the transformation or inner journey of a character over the course of a story.” Further on in this chapter, we’ll look closer at character arcs and character development.

One of the reasons why it’s so important to pay close attention to your characters is summarized quite well by director and cinematographer Samo Zakkir:

If you’ve done your homework, really enveloped yourself within the character iceberg, and you know your characters intimately, the rest is easy. The character tells you. All you have to do is listen.8

This is something we can learn from when it comes to product design.

The Role of Characters and Character Development in Product Design

When we talk about characters in relation to product design, we often think of personas, whether they are user personas used to represent key user types, or marketing personas (also referred to as buyer personas) used to represent ideal customers. Today, however, there are a growing number of types of actors and characters to consider. For example, new input methods are present in the form of voice UIs and conversational UIs, with the “system” increasingly taking on human traits through the form of AI and machine learning.

Many roles that were previously filled by people, such as the support team over the phone, are now handled via chats and bots through AI and machine learning. Though we may not automatically think about it, whether we like it or not, and whether we define those personalities it explicitly or implicitly, users will infer some personality on each point of interaction. The way the bot writes and the way a VUI sounds impacts a user’s perception of the same, and that perception matters because it impacts a user’s emotional response. We should define intentionally rather than leave up to the users to interpret on their own, because it impacts the success of the experience as well as the brand. As brand strategist Jess Thoms writes, “If you don’t spend the time crafting that character and motivation carefully, you run the risk of people projecting motivations, personality traits, and other qualities onto your App and brand that you may not want associated with them.”9

Regardless of whether our products and services involve a conversational interface, the case for defining the characters and actors is less about avoiding users projecting unwanted characteristics onto our products and services and more about acknowledging that personality, and a growing number of actors, increasingly play a role in the product experience. Additionally, it’s also about really understanding the people who we’re designing for.

Just as Walt Disney paid attention to the smallest of details as well as the whole, we need to do the same. To truly cater to user and business needs, and to address the challenges we covered in Chapter 3, we need to take ownership of the bigger picture as well as the small details in the products and services that we design. That has a lot to do with understanding what plays a role for whom, when, and where, and that “what” is increasingly related to a particular “who.”

In this chapter, we’ll look at the importance of characters and character development in relation to product design.

The Role of Characters in Creating a Shared Understanding

One of the main reasons to pay attention to characters is to ensure that everyone is on the same page when it comes to who we’re designing for. As an extension of that, we want everyone involved to know personas we’re working with. Making sure that the team and the client, if applicable, share a deep understanding of who you’re designing the product for, and what matters to those people, is critical. This knowledge ensures not only that you’re developing and designing the right thing, but also that you get buy-in for the solutions that the team is proposing and that they indeed get implemented.

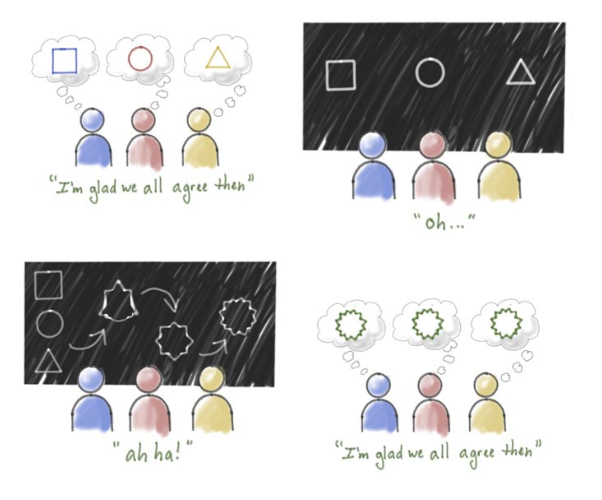

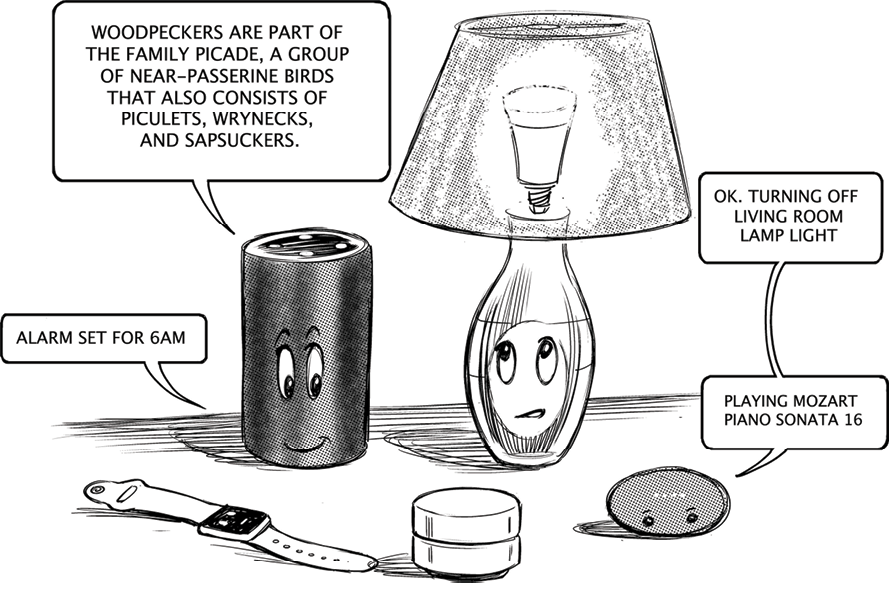

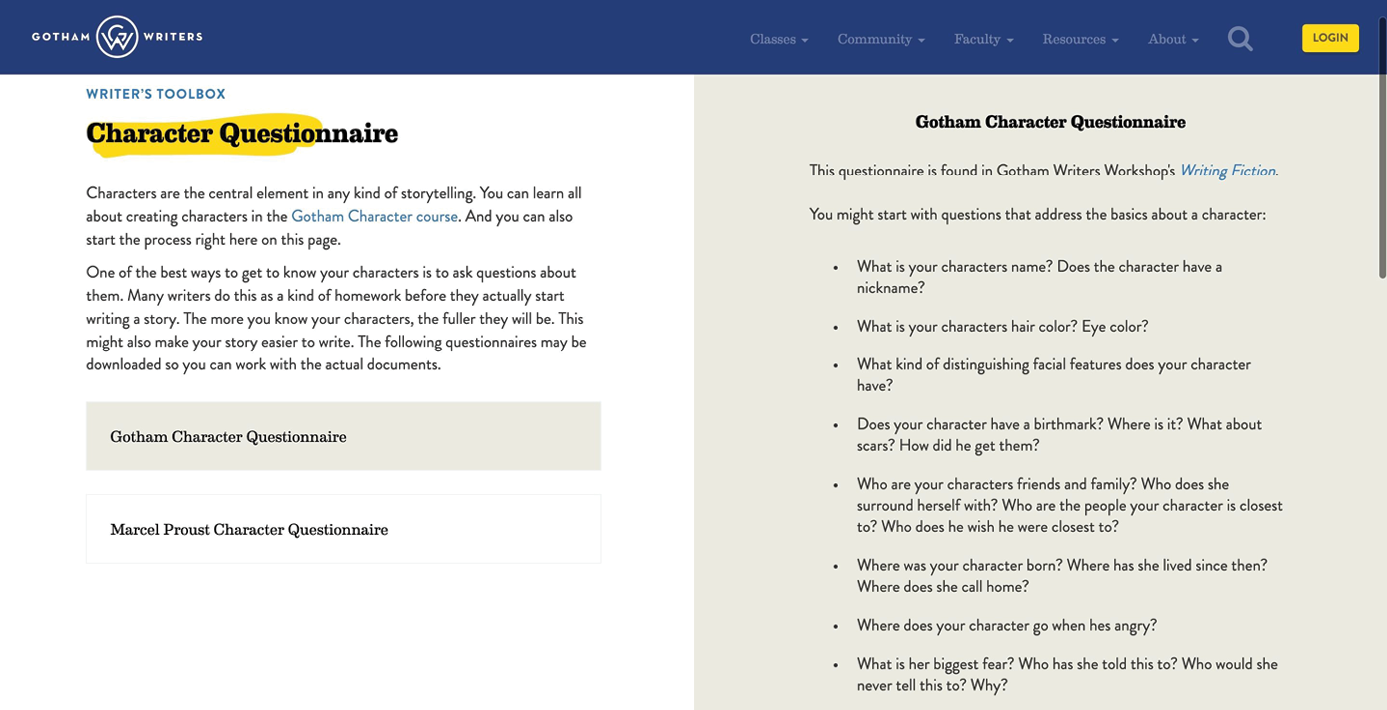

A famous picture by Luke Barrett is used in numerous articles about personas and proto-personas (or ad-hoc or improvised personas as they are also called), and the importance of having them articulated (Figure 6-1).

Figure 6-1

Cartoon by Barrett illustrating the importance of shared understanding

Having well-defined personas ensures that the internal team and that of the client have a shared understanding of who you’re designing for and what they need, rather than each person walking around with their own understanding in their heads.

The Role of Characters in Creating Empathy

One of the reasons character development in product design is so important is that it includes the characters’ emotions. Bringing these emotions to life through the character is one of the most powerful ways of reaching an audience.

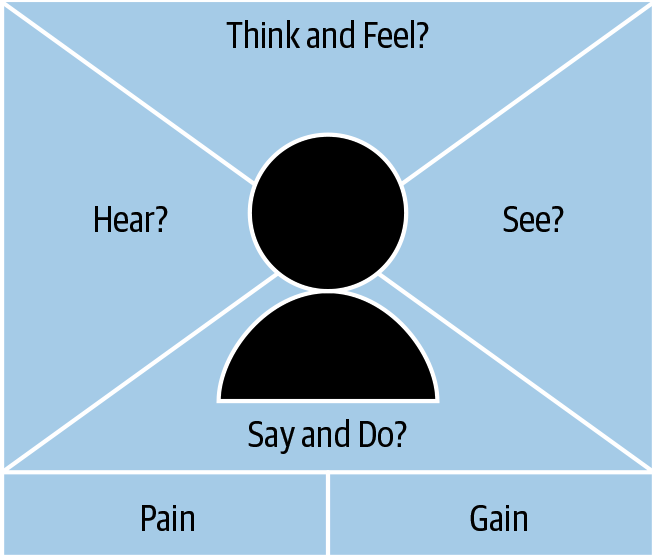

In product design, we often talk about the importance of empathy. Empathy is about being able to see the world through the eyes of others, and as best as possible to imagine what they see, think, and feel. Empathy maps, shown in Figure 6-2, are one type of tool used to help create this understanding. IDEO’s Human-Centred Design Toolkit defines empathy as a “deep understanding of the problems and realities of the people you are designing for,” and the importance of it lies in being able to set aside our own preconceived ideas.

Figure 6-2

An empathy map, which is used as a low-fidelity tool to help create empathy and understanding for the users of our product and service

As mentioned earlier, personas have been getting a bad reputation as of late for being superfluous and not adding anything to the design process, but instead simply being a deliverable that gets shoved away in a drawer after they’re done. Part of that is related to the process in which personas are created. In my view, a lack of true empathy for the people we design for, and their personification through personas, also plays a role. We tend to focus on the functional bit in terms of features, and even though we work with user stories or JTBD that include a qualification of the requirement, without linking these to a personification of a user, they tend to be too generalized.

Just as we need to connect emotionally to the characters in a story for it to have an effect on us, in product design we need to connect emotionally with the people we’re designing for. Beyond making sure that we see the needs of the people we design for through their eyes rather than our own, empathy is also critical for getting other people vested in the process and vested in the people we’re designing for. Without empathy, we don’t care, and if we don’t care, then we won’t bother paying attention to the personas, or use them in the product design process. And without that, the end result is very likely to fail to meet the needs, motivations, worries, barriers, and more of the people we’re designing for.

The Role of Characters in Understanding Needs and More

The more we define experiences that need to work for specific users, their devices, and scenarios, ensuring that it fits into the users’ own personal stories, the more we need to understand the specifics of the users. Our aim should not be to define a user group as a whole, or to define a one-size-fits-all solution, but to really understand who our customers are and what they need at specific points in their journey. Only then can we make them the true heros of the experience.

As we’ve talked about throughout this book, users now expect experiences that work for them, and them specifically. As advances in technology progress, with devices and experiences on these devices that increasingly feel like they know us, the more this expectation of “just for me” is going to increase.

As Alan Cooper, founder of Cooper Professional Education, “Father of Visual Basic,” and inventor of design personas, says: we need to look at personas as individual users and dig in deep to identify what matters to them, how the experience should feel when and where, and the overarching principles that should guide the story that we’re telling that specific user.

The Role of Characters in Helping Define the Product Experience Narrative

For script writing, it’s often said that your story will come to life only when you know your characters inside out and can imagine them in every possible situation, from the mundane to the extraordinary. That same principle applies to creating product and service experiences that truly meet user needs. When you get to the point where you can imagine the relationships your users have with others (including the product), how they’d behave and react, and what they’d need in certain situations, you start to really explore the world of your product’s story. Then just like that, scenes start to emerge that will help inform the experience narrative, what it needs to include, when, and how.10

The Importance of Identifying All the Characters and Actors in the Product Experience

Think back to the sequences, scenes, and shots we covered in Chapter 5. For every scene in a play, movie, or TV series, certain members of the cast have to be present. They have a particular part to play, lines to deliver, actions to perform, and often a specific place (or mark as they are called) to be at a specific time for everything to come together and for the hero’s journey to progress. It’s choreographed and designed, and everyone is, clear on who the cast is and when the different actors are supposed to be on set/stage, and what roles they have.

That same kind of choreography and cast approach is immensely beneficial to product design as well. For every scene of a product experience, certain “cast members” need to be present. It may just be the user, but more often than not, more characters and actors play a part than we immediately think about, as we’ll be looking at next.

The Different Actors and Characters to Consider in Product Design

Usually, more actors are at play than you would immediately think when it comes to product design. We see this in traditional storytelling as well. The majority of stories have more than one character, even if some of these other characters aren’t actual people.

In Cast Away, Wilson the volleyball serves as Chuck Nolan’s (played by Tom Hanks) sole companion during his time on the desert island. The character of Wilson the volleyball was created by screenwriter William Broyles Jr., and from a screenwriting point of view, Wilson helps ensure realistic one-on-one dialogue in the otherwise one-person situation presented in the majority of the film. Similarly, a character that isn’t a person plays a big part in the movie Her. “Her” refers to the operating system that the main character, Theodore (played by Joaquin Phoenix), develops an unusual relationship with. Though Samantha, as the operating system is called, has dialogue and is played by Scarlett Johansson, you never see her.

Just as the hero will meet people on their quest, the users of our products and services will always come across different “characters” and actors on their journey. The users will see the characters that play a part in the products and services we define—from first hearing about our product or service, to whatever and wherever the end of that experience story will be. These characters will vary based on the type of product or service. The following is a good starting point to help you see the “who” and “what” that may need to be considered as part of your product’s cast of characters and actors:

The user

The user is the protagonist and the hero of our product or service.

Other users

The actions of other users (e.g., commenting, liking, posting, etc.) have an effect on the user’s experience.

Friends, family, partners, colleagues

Friends, family, partners, and colleagues are the allies that the user turns to for advice, or to share joys and frustrations with.

The system

The software systems, or external software system, with which the user or other systems interact.

The brand

The brand can be personified through TOV, look and feel, a VUI, animations, messaging.

Bots and VUIs

Bots and VUIs are part of both the system and the brand, but they are treated separately because of their prominence and distinct personality-based characteristics.

AI

Also part of the system and the brand, but treated separately because AI needs to be taught, initially, by people.

Touch points and drivers

Touch points and drivers include the people, platforms, interactive installations, points of sale, physical stores, etc., that users will interact or engage with on their journey with our products and services.

Devices

Devices are all things smart that are more than a mere “prop” and whose “when,” “where,” and “how” play an actual role in an experience; for example, smart phones, smart watches, smart home devices, and IoT.

The antagonist

The antagonist isn’t always visible, physical, or digital, but present by putting obstacles in the way of what the user is trying to accomplish. Can be internal (e.g., doubt) or external.

Next we’ll take a look at each type of character in a little more detail, in terms of what to consider and why they play a part. Before we do that, however, we need to define what a character is when it comes to product design and distinguish between characters and props.

A Definition of Characters and Actors in Product Design

In traditional storytelling, the distinction between characters and props isn’t so much of a problem. A prop is “an object used on stage or on screen by actors during a performance or screen production. In practical terms, a prop is considered to be anything movable or portable on a stage or a set, distinct from the actors, scenery, costumes, and electrical equipment.”11 However, as the following examples demonstrate, some props in traditional storytelling will at times be treated as characters in product design.

A character, or actor, in product design can be defined as someone who plays a direct part in one or many of your product’s storylines and scenes. They should also be present for the scene to work as intended.

|

[ NOTE ] I say “should be present” and not a “must be present” because the particulars of any given project always depend on the needs and specifics of that project. |

Throughout the rest of this book, we’ll work with the following definitions when it comes to characters and actors in product design:

Characters

Personified players in the product experience that interact with or influence other characters, one of which may be our protagonist, the user

Actors

Nonpersonified systems that the product we’re working on interacts with or depends on

Props

Elements—stationary or movable—that are used by characters or just in the product and that help further the action of the product experience

The Users

Just as there has to be a protagonist present in a story (or there wouldn’t be a story), when it comes to product experiences, there wouldn’t be any experience or product to speak of if it weren’t for the users (Figure 6-3). You’ll have primary, secondary, and, at times, tertiary users for any product. Whether we place a primary focus on them and their needs, or cater to them as a secondary audience, they are the ones the product and service is really about.

There’s an ongoing debate in the UX field of what to call, or not call, users. Throughout this book the term “user” is used in a broad and general sense, complemented with the following distinctions:

Users

People who—in the past, present, or future—will use our product or service, but might not necessarily complete a monetary transaction in doing so.

Customers

People who either paid, are currently paying, or will pay for our product or service. Customers, however, will not necessarily have used the product.

Audience

Passive “onlookers” who are either indirectly or directly subject to our product or service; for example, through marketing.

Figure 6-3

The users

The Other Users

The majority of stories have supporting characters that help either the protagonist or the plot of the story. In product design, and experiences in general, there are always other users who form part of the main user’s team, company, or network—either on a first-, second-, or third-degree level. The main user may have no connection to them other than a shared interest, topic, or location that connects them indirectly. For example, the other users might have left a review or comment, or all be part of the same Slack group or local Facebook group (Figure 6-4).

The other users are generally important when products have a social aspect (e.g., LinkedIn and Slack). They also play a significant role when trust in the product and its offering is influenced by other users’ reviews or comments (e.g., about a positive or negative experience on an ecommerce or restaurant site).

Here are some examples of other users to consider:

Peers

Users who are similar to the main users. They can be active or passive; for example, first-, second-, or third-degree contacts on LinkedIn or members of a Slack channel.

Contributor

Users who have an official role that involves creating content or in other ways adding to the product; for example, a contributing writer for your product’s blog.

Passive users

Users who don’t create or add to the product or service offering but engage through simply using the system in its intended way; for example, liking things on Facebook but not posting updates or content on their own.

Influencers

Power users and/or early adopters with a large audience who actively share or contribute by creating content, sometimes in a formal capacity as someone hired by a brand or as their main job; for example, a YouTube or Instagram creator who is considered to be one to follow related to a topic.

Promoters

Users or customers who are advocates of your product or service and who can influence others; for example, sharing a positive message related to your product or service on their social accounts.

Detractors

Users or customers who are critical of your product or service and who can influence others; for example, sharing a negative message related to your product or service on their social media accounts.

Though other users will almost always play a role—at least as promoters or detractors—there are a number of types of products where they don’t have any impact on the user’s experience or use of that product besides influencing a decision to go with the product and company in question. Accounting software for freelancers and banking are two such examples where the other users might recommend a specific software but aren’t part of the product experience beyond that.

Figure 6-4

The other users

Friends, Family, Partners, Colleagues

In traditional storytelling, friends, family, partners, and colleagues are often some of the other main characters (Figure 6-5). Because they are the people closest to the protagonist, they usually play a big part in the protagonist’s life.

In product design, friends, family, partners, and colleagues tend to be the main user’s most trusted allies. They are the ones whom the user turns to for advice and recommendations, and whose opinions the user seeks out (or in some instances doesn’t seek out but still gets). Though they play a big role in the protagonist’s life, in product design these characters tend to take on more of a one-string character form, appearing in only one part of the product experience; for example, research.

Figure 6-5

Friends, family, partners, colleagues

However, friends, family, partners, and colleagues can become more like subplot characters when a certain part of the product experience story involves both them and our protagonist, the main user. The main user might consult with others when making a decision on whether to buy one product over another, or seek help with setting it up. In many cases, the role they play doesn’t involve any direct engagement with the product itself. Instead their part usually concerns an offline experience, such as offering advice on whether to buy the product or not.

Considering friends, family, partners, and colleagues in the product design experience is important mainly because of the role they play in influencing the user’s key decisions by providing subjective opinions (or objective ones, for that matter).

The System

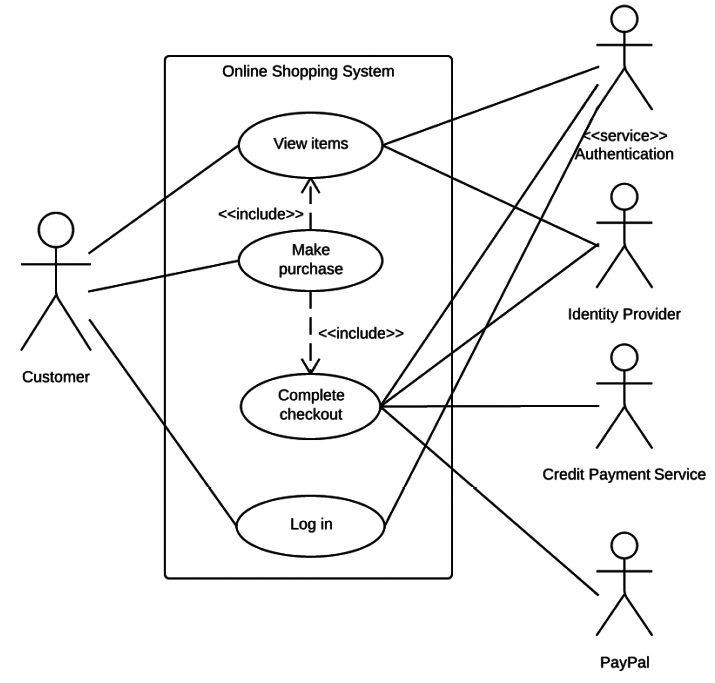

As we covered earlier in this chapter, the system, or more precisely the operating system called Samantha, was one of the main characters in the movie Her. Back when I studied computer science and business administration at Copenhagen Business School, one of the subjects we studied was systems analysis and design. We created Unified Modeling Language (UML) diagrams and use case diagrams, and the system and its components (including the database system, client application, application server, etc.) were defined as actors and represented as little stick men.

The purpose of use case diagrams is to identify the ways a user might interact with a system (Figure 6-6). It’s not a detailed step-by-step representation, but a high-level overview of the relationships between use cases (e.g., make a purchase or log in), actors, and systems.

Figure 6-6

Example of UML use case diagram

When we talk of actors in relation to the system, there are both primary and secondary actors (Figure 6-7):

Primary actors

Actors who use the system to achieve a goal; for example, the user, or customer referred to in Figure 6-6.

Secondary actors

Actors who the system needs assistance from in order for the primary actor to achieve their goals; for example, PayPal, or the Credit Payment Service shown in Figure 6-6.

Figure 6-7

The system

Because we are referring to the main user as either the “user” or the “protagonist” throughout this book, instead of as “primary actors” as per the preceding definition, we’ll use the following definitions of “system” and “actors” in product design:

System

The product or service that we’re working on as a whole and when this acts intelligently and communicates with the user; for example, Gmail and its “Received 5 days ago. Reply?” nudges.

Actors

Other systems or technical actors that the system needs assistance from in order for it to enable users to achieve their goals; that is, the same as “secondary actors” in the preceding definition; for example, payment gateways, using existing login systems like Facebook and Gmail.

The Brand

As we discussed in Chapter 1, storytelling was one of the earliest forms of branding. Anyone who’s worked with branding is used to defining and giving the brand a personality through the TOV and the look and feel. We define what the brand should and shouldn’t say in terms of the language that is being used and what it should look like in terms of colors and the imagery style.

With the rise of bots and VUIs, the personality of the brand (Figure 6-8) is increasingly more important. Though we’re far from the world that we saw in the movie Her, we’re not that far from it. As technology takes on more human traits and becomes more intelligent, defining the personality of the brand—the dos and don’ts in terms of its behavior—is becoming more important for ensuring that we deliver the right experience to our users and customers at the right time.

Figure 6-8

The brand

Who and what the brand stands for should be communicated and felt by the people using the product in ways beyond the TOV and look and feel. Both should be apparent in micro interactions, in error messages, and micro copy. It should also be part of how the brand behaves across different input methods and touch points.

In some cases, including with VUIs and products that have chatbots as part of the experience, the brand will increasingly be one of the main characters, or at least a key supporting character. However, even when the brand takes on a more prominent role with its presence, it should never be the hero. The hero is always the user. The user is who the story is about, and that’s why the product exists.

When we’re talking about “brand” in relation to character, we’re talking about the brand’s overall personality, which in particular can be seen and felt in the following ways:

The brand’s TOV

From micro to long-form copy

The brand’s look and feel

From color palette to animations

The brand’s conversational UIs

From text and avatar-based to voice-based personifications

Any other personification of the brand

Customer service representatives, sales reps, etc.

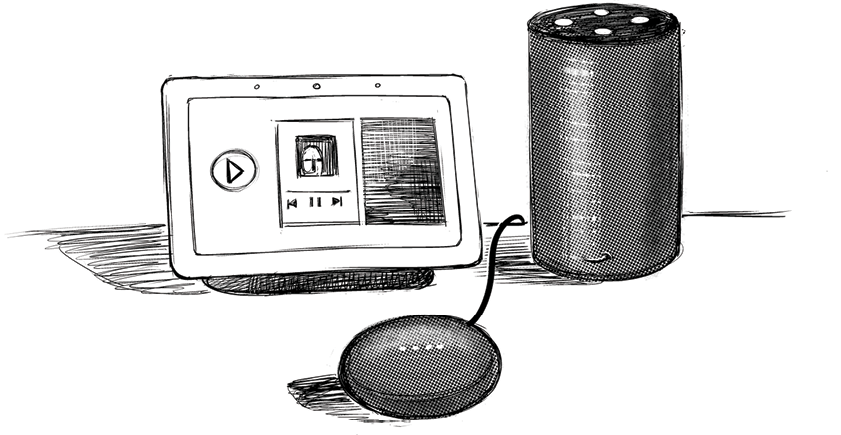

Bots and VUIs

In the movie 2001: A Space Odyssey, the computer HAL 9000 speaks in a soft, calm, and very conversational manner. Yet, when combined with its face plate and actions, it becomes quite clear that HAL 9000 is an antagonist. As soon as something is given a voice, whether an actual voice or in written format, it needs a personality. Whether we like it or not, people will project human traits onto anything that has a voice or human characteristics, such as a bot interface.

As Oren Jacob, founder and CEO of PullString, says, “We cannot separate having a conversation from thinking about whom we are having that conversation with.”12 Everyone we’ve talked to, or as Jacob points out, everyone who has talked to us—has had a personality, a tone, a mood, and a style that’s influenced the way they talked. When we communicate, he says, we communicate both above and below the surface. What’s said below the surface, in the subtext, often makes up the majority of our long-term perception of the experience. We’re accustomed to using subtext to read the people we talk to, and we can’t help but use the same strategy to understand bots and VUIs, too (Figure 6-9).

Figure 6-9

Bots and VUIs

When we talk about the personification of bots and VUIs, we consider both the nonseeing aspect and the seeing aspect. Some bots have an avatar, whereas some conversational interfaces consist of just a voice or text from which we infer the personality. Whether we see or hear something talk back to us, it’s only natural for us to project human traits onto it. This personification triggers us to start building our relationship with the thing in question.

As mentioned earlier, this personification will happen regardless of whether we like it or not. Therefore, it’s to the product’s and the users’ advantage if we put some actual work into it. We have the opportunity to make chatbots and VUIs particularly effective by creating them to match the situations, contexts, and outcomes that we need them for—and increasingly, we have to define their personality.

Some of the aspects that we create personalities for bots and VUIs through are:

The bot or VUI’s TOV

How it talks or writes in general

The actual voice of the VUI

Making sure it matches the defined TOV and the product

Situational responses

What and how it responds in various situations, both happy and unhappy ones

Behavior

If and how it should behave differently under certain circumstances; for example, when specific subjects are asked about

Appearance

What the personification should be, considering the type of product

AI

When it comes to making a distinction between bots/VUIs and AI in traditional storytelling, the waters get a bit muddied. Without an actual voice to the AI, there wouldn’t really be an AI to personify (Figure 6-10). Ava, the robot HAL 9000, and Samantha in the movie Her are two other examples. However, I’m treating the AI separately because AI needs to be taught and we have a responsibility in teaching it well.

What AI is really good at is dynamic personalization: it can tailor specific recommendations based on a user’s actions, or lack thereof. What AI is really bad at is understanding nuances and filtering them out, as well as responding in a humane way, which requires empathy.

Increasingly, designers will be less of the creators but more of the curators of the AI. It’s our job to ensure we bring an empathetic context to the AI as well as establish what relationship the AI should have to the product and the user.13

Figure 6-10

A representation of AI inspired by 2001: A Space Odyssey

When designing AIs, we need to be particularly aware of the following:

What AI learns from

AI learns from what is fed into the system. If it’s told only about apples, it will deal only with apples. As designers, we need to be on the lookout for bias in the data we feed into the AI.

Understanding user states

Currently, AIs aren’t great at identifying, understanding, or responding accordingly to different user states such as sad, happy, angry. Until we reach a point where they are and can adjust and respond in empathetic ways, some scenarios will be better handed off to humans.

Devices

Devices and technology have so far played a primary role in sci-fi literature and in movies like Her and Iron Man. In these stories, devices often play the role of assisting in the main protagonist’s endeavor. They are more than mere technology that the protagonist uses, and the words assistant, companion, or extension of [the user] describe them better.

The more advanced that AI and machine learning get, and the more integrated they become in driving real value in product design, the more devices move from being a prop to being an actor or character in the product experiences that we design (Figure 6-11). We covered bots and VUIs earlier, and smart speakers are an obvious example of a device as a character. There are, however, many more. What makes a device a character rather than a prop is its role as a personified players in the product experience that interacts with or influences the main user, or other users.

Figure 6-11

Devices

Here are some examples of devices as characters:

Smartphones

What makes the smartphone a character rather than a prop is the enabler aspect of the device and that its role can change with the context of use. The more intelligently the operating system acts, the more helpful the device becomes and the greater its role (e.g., the Pixel and Android 10).

Smart watches

These devices often play a very similar role to smartphones, though generally more akin to an assistant that notifies you of key things because of the limitations in the tasks you can carry out on the device. Just like smartphones these devices are highly personal (e.g., Apple Watch).

Smart speakers

These often get referred to by name. Though very closely linked to the AI that powers them, they become a character in themselves that lives in a specific place in the home (e.g., Amazon’s Alexa and Google Home).

Robots

Though very few of us so far have robots in our home, these devices, similar to smart speakers, will often perform a specific role or task (e.g., the Roomba vacuum cleaner, and mobile webcams that let you speak to your pet).

IoT

A good way of thinking about IoT as characters is to think of IoT as objects that talk to each other and hat we can interact with by using voice, an app or other means (e.g., Nest and Hive).

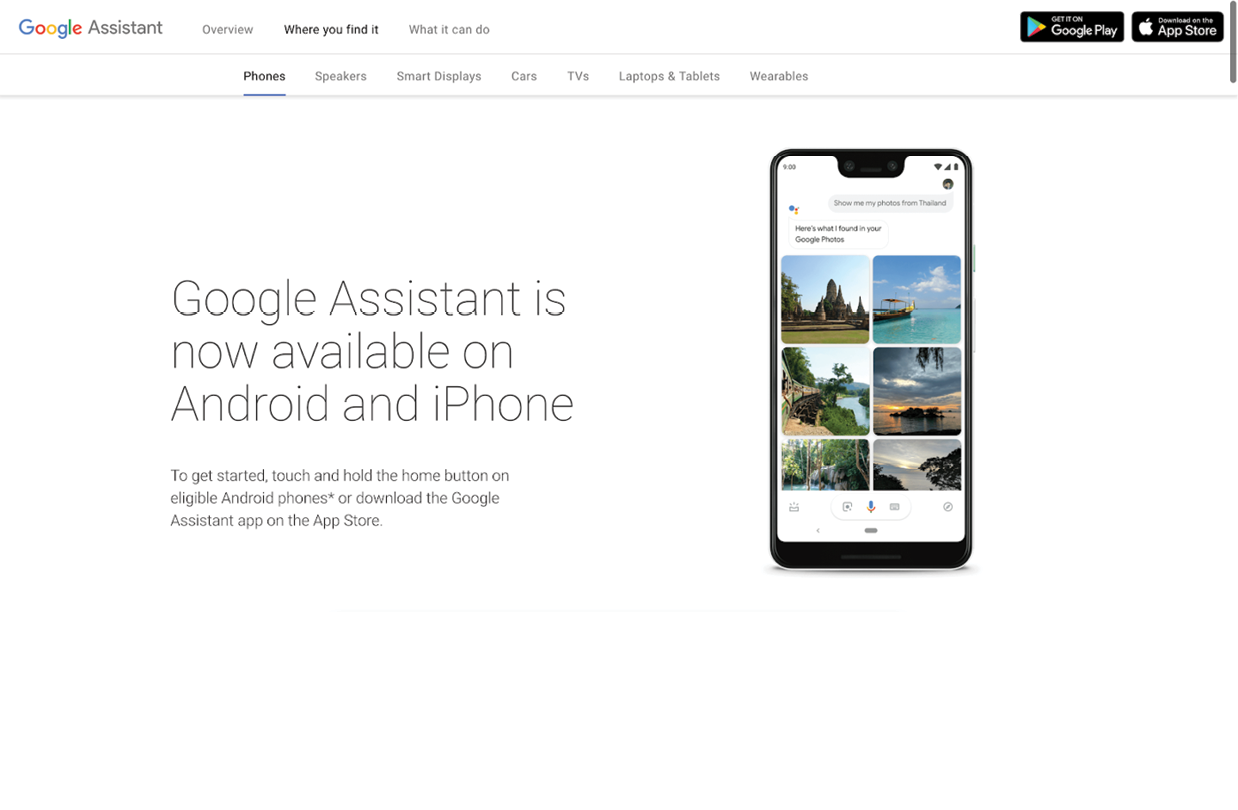

As these examples show, a very close connection exists between the device and the product that the user is using on the device, as well as a connection with the AI that powers it. However, maintaining a separation between them during design is still important, as the specifics of the device itself will have an impact on the “how” and “where” of the user’s experience. For example, the use of Google’s voice assistant on a smartphone has a different context than the use of Google’s voice assistant on a smart speaker (Figure 6-12). With this in mind, devices should be thought of as the enabler to the product or service.

Figure 6-12

The Where to Find It section on the Google Assistant website showing all the types of devices that have Google Assistant available

Touch Points and Drivers

In all stories, the protagonist comes across other people in the journey. These people have a role to play, however minor: in one way or another, they assist (or try to sabotage) the protagonist’s quest. Similarly, all experiences include multiple “meet-along-the-way” touch points and drivers that the user will come across (Figure 6-13).

Some touch points are involved in creating awareness and in driving action (or no action), around the product in question, while others are best thought of as props that are present but don’t really play an active part in the scene other than to further the action. An example is an ad that you see in a magazine or online that may remind you or nudge you into doing a Google search. Though these touch points are important, the touch points and drivers that are of interest when it comes to characters and actors are those that play a more active role. These touch points are more akin to minor characters in traditional storytelling.

Figure 6-13

Touch points and drivers

We defined touch points and drivers as the people, platforms, interactive installations, points of sale, physical stores, etc., that users will interact or engage with on their journey to and with our products and services. What these touch points and drivers have in common is that, in one way or another, they have a message or opinion directly or indirectly associated with the product or service that may influence other people’s opinions and actions. That opinion may be good or bad.

Here are some examples of touch points and drivers:

Direct touch points and drivers

Any touch point that has a voice, albeit not necessarily a physical one, and that the user interacts with through a more active choice and as such helps drive their journey (e.g., blogs, news sites, magazines, ads that the user clicks).

Indirect touch points and drivers

Any touch points that the user comes across and that they don’t actively interact with, but that still may influence the user through their messaging (e.g., billboards, ads that the user doesn’t click).

The Antagonist

In traditional storytelling, the antagonist is the person who wants things to go badly for the protagonist. They might take direct action to sabotage the protagonist (Figure 6-14).

In product design, we often don’t think about antagonists, and we often design for the best-case scenarios. However, there are multiple antagonists to consider:

Internal antagonists

The “devil-on-the-shoulder” thoughts and feelings that influence users in a negative way in relation to taking action or achieving their goal (e.g., the user’s doubt or lack of confidence in their ability to succeed).

External direct antagonists

Those that actively attempt to sabotage the main user (e.g., trolls and haters on social media that post negative comments in reply to the main user, or about the product with the aim of causing pain).

External indirect antagonists

Those that are indirect in that they don’t assist the user in achieving their goals (e.g., badly written error messages or instructions that confuse users rather than guide them).

Figure 6-14

The antagonist

This overview is a helpful reference for identifying the characters and actors in a product experience. The next step is to define and develop these characters and actors further.

The Importance of Character Development

One of the main goals in traditional storytelling is to create characters that the audience or the reader will care about. Without such characters, there usually isn’t a good story, and if there is no emotional connection, then the story will fall flat. Screenwrite and director John Truby says that one of the biggest mistakes writers make when developing their characters is to make them as detailed as possible by giving them too many traits. According to Truby, these are just superficial elements of a person. Though they help us see who the character is, they’re not what makes us care about a character.

What makes us care are two things: the character’s weakness (i.e., the need of the character and that deep personal problem inside), and the character’s goal in the story (which will eventually also deal with their weakness and problem).14

The goal, or objective, of the character is an important aspect of who the character is and how they will develop. Each character will have one, just as each user will have an objective when it comes to product design. This objective is also related to the big “why.” We’re always advised to dig into the “why” in product design. In traditional storytelling, the why is an important part of establishing why the character is in the story and, in turn, who they are.

By trying to answer the questions that we have around the characters, or users, we start to do our research into their context, culture, and occupation. We start to add in details around their values, attitudes, and emotions, and we develop the characters’ backstories covering physiology, sociology, and psychology. With these details (partly) defined, their personality and behavior become defined, and you can imagine them in a range of situations, from the extraordinary to the mundane. And then all you have to do is listen, as I said at the beginning of this chapter. The characters will help tell you their story.15

Next let’s look at a few terms that often appear in discussions about character development in traditional storytelling.

Dynamic Versus Static Characters

In traditional storytelling, a distinction is made between dynamic and flat characters. Dynamic characters go through some form of change that can be seen. Most protagonists are usually dynamic characters.

Static characters, in contrast, don’t change throughout the course of the story. Instead, they remain the same and serve to ensure contrast to the dynamic characters. Antagonists are often static characters.

Round Versus Flat Characters

Related to dynamic and static characters are round versus flat characters. Round characters are fully developed and show a true depth in personality. They are often complex and more realistic and undergo changes that at times may surprise the audience or reader.

Flat characters have less depth to them. They are two-dimensional and relatively uncomplicated. They don’t usually undergo any changes but remain the same throughout the work.

Character Arc

The changes in a character are often referred to as the character arc, which Wikipedia defines as “the transformation or inner journey of a character over the course of a story.” Essentially, if a character starts as one person and changes, that’s a character arc. Though less important characters can have a character arc too, the character arc is most common for the protagonist and the lead characters.

There are also different types of character arcs:16

A change arc

The classic “hero’s journey,” where the character changes from more of a nobody into a hero. The change that is happening here is transformative and most aspects of the character change throughout the story.

The character overcomes an inner battle (e.g., a weakness or fear) while facing external opposition. At the end of this “change,” the character is a fuller person but otherwise the same.

With a better understanding of these terms, we’ll take a look at what traditional storytelling teaches us about making the characters come to life.

What Traditional Storytelling Teaches Us About Characters and Character Development

Some stories will begin with the plot and narrative evolving around the characters, their needs, motivations, weaknesses, and secrets. In these types of stories, the trick is to make sure that the story that unfolds doesn’t result in “a beginning, a muddle and an end,” as the author and poet Philip Larkin says. More often than not, however, novels will begin with an idea for a story. Some writers, or pantsers as they are also called, prefer to just sit down and write the story as it comes to them. To them, the characters will develop as the story unfolds. Others, the outliners who prefer to outline their novel or book first, will know a lot more about the characters before they start writing. We’ve previously referred to this as character-driven versus plot-driven stories. Regardless of the approach you take, characters need to be defined and developed.

Whether you’re working on a film, TV show, book, or animated movie, the advice is often to draw from your own personal experience when you build out your characters. It’s quite the opposite when we talk about product design. For product design, we’re often told that we are not our users. While drawing from own experience is a great starting point, both product design and, traditional storytelling emphasize the importance of research. To develop well-rounded and believable characters, you need to not only be able to describe them, but also know the motivations and reasons for their actions, thoughts, and feelings, and how these, in turn, affect the protagonist’s friends and family. You’re not as likely to get these details just by doing online research, but may need to have face-to-face conversations.

As for how to develop and introduce characters, you can take insight and inspiration from the way characters are developed in books, animations, games, TV, and film scripts, and in how actors make them come to life.

Building and Introducing Characters in Books and Novels

In novels, the advice is to introduce your characters slowly. The main character is the one you should meet first, and many writers make the mistake of introducing them too late. Not everything about the character should be described with words, however.

Novelist Jerry Jenkins says that imagination is part of the joy of reading and that you should trust your readers to deduce the qualities of the character through what they see in your scenes and hear in your dialogue. The old saying “Show, don’t tell,” Jenkins explains, applies here too. “Show who your character is through what he says, his body language, his thoughts, and what he does.”17 Furthermore, don’t force your readers to see the character exactly the same way you do. It doesn’t matter if your audience imagines your main character with dark or blonde hair, Jenkins says:

Thousands of readers might have thousands of slightly varied images of the character, which is all right, provided you’ve given him enough information to know whether your hero is big or small, attractive or not, and athletic or not.

What will help your readers, however, is to give your character a tag, a repetitive verbal device, as many readers will struggle to differentiate one character from another.

Applying it to product design

We recognize the use of tags from the personas we work with in design. We often give them a name that helps us put them in perspective in terms of the product or service we’re working on, as well as in relation to the other personas. For example, we may have “Sarah, the social shopper” who’s different from “Karen, the carefully considered shopper.” Giving our key users these tag lines helps us remember who they are and what distinguishes them from other users.

As for how to introduce your character, the advice for novels doesn’t apply to product design. In product design, it is important that the core team, clients, and key stakeholders share a common understanding of who the users of the product are from the start of a project, as the image by Luke Barrett earlier in this chapter illustrated. Everyone, and the core team in particular, should be able to reference who the main users are without looking at the deliverable that specifies this. Some seeing the user with brown hair and others seeing the user with blonde hair is less of an issue, but sharing the same deep understanding of who you’re designing for is crucial. We can take this lesson from traditional storytelling:

The goal is to make your readers feel something for your character. The more they care about them, the more emotion they’ll invest in your story. And maybe that’s the secret.18

Well-Developed Characters for TV and Film

Many of us have read a book that was later made into a movie. Sometimes it’s a disappointing experience. What was magical when we read it does nothing for us when we see it up on the big screen. This difference might come down to the way the film is directed. Other times the problem lies with the cast and the characters. Maybe they’re too different from what we imagined in our heads when we first read the book. Or maybe they simply don’t connect with us.

In storytelling, it doesn’t matter how good the plot is in principle, if it’s not brought to life through the characters of that same story. This is of particular importance when it comes to film, TV, and theater, where the images created in our heads by the words we have read in a book are replaced with what we see on screen or on stage. If the characterization falls flat, or is badly acted, then the storyline will become unbelievable and we won’t connect emotionally.

In contrast, if the characterization is really well done and acted, it can make the whole film or TV episode/series. The movie Gone Girl, based on the best-selling book of the same name, is a great example. The character of Amy Dunne, as written in the novel and as portrayed onscreen by Rosamund Pike, is one of the most frightening and hated villains.19 Another example of well-developed characters is the American drama series True Detective. Here every character has intentions and obstacles that help make them feel like living and breathing people.

True Detective creator Nic Pizzolato says that bad writing looks like characters running around delivering and trading information with no life in the plot. Daniel Netzel, who makes videos about movies and publishes them on Film Radar on YouTube says Rogue One is an example of this. One of the reasons for its flat characters stems from the way director Gareth Edwards, approached making the movie, Netzel says: “Most of the sequences felt like they were there to serve the purposes of the writer, and not the characters.”20 This assessment fits rather well with the way Edwards describes his approach himself:

The way I like to work is, you try and come up with visual milestones of like...Well I’d love to see this, and I’d love to see this, and I’d love to see this. I’m not sure how they’ll connect. And then what you do is, you create visuals of the things that would be great. And then you try and find a way of linking them all in.

According to Netzel, this is a mistake: although this process can certainly produce something that’s visually stunning, like Rogue One, a plot that is driven by the aesthetic needs of the writer or the director rather than the characters’ motivations will inevitably leave us feeling that something is missing.

Director and producer Ridley Scott, who has a background in directing commercials, is another example of a director who is famous for being more interested in the shot and how it looks than how the characters develop. That’s not to say you can’t produce a box office hit this way. Both Rogue One and the Alien movies show that you obviously can, but focusing on the shot is not what’s going to create the strongest emotional connection, and that, as we’ve covered, is where the power of stories lie.

Applying it to product design

Moviemakers and writers can forget about the power of a character’s emotional development and instead get swept up in specific scenes, or in including high-tech special effects.21 Likewise, in product design we can get too excited about the latest animations or design trends and forget to question whether they are right for our users. Or we let features, “the big idea,” or business requirements drive our work instead of anchoring it in the users’ needs and goals and the bigger “why.”

To deliver product experiences that really engage the user, and to get the product design process to be really user-centered, it has to be a character-driven (i.e., user-driven) experience instead of a plot-driven (i.e., idea-driven) product.

As for working with character-driven plots and developing characters, novelist Stephen King advises to “put interesting characters in difficult situations and see what happens.”22 This is along the same lines as the general advice for script writing that we referenced earlier: your story will come to life only when you know your character inside out and can imagine them in every possible situation.

Actors and Building a Character

Drama schools teach a number of techniques to help actors empathize with the character; this empathy helps create believable emotions and actions in the characters that they portray. One of the methods is the Stanislavski method, which is used to build believable characters in seven steps by asking these questions:

- Who am I?

- Where am I?

- When is it?

- What do I want?

- Why do I want it?

- How will I get it?

- What do I need to overcome?

The method is based on first reading the script carefully to get a good understanding of the character’s motivations, needs, and desires, and this in turn helps the actor identify the role that they’re playing. After that, the actor starts working out how the character would behave in situations and how they’d react. The actor must keep in mind the character’s objective, and the obstacles that stand in the way of achieving their objective. These also determine just how far they are willing to go to get what they want. The actor is advised to break down the script into beats, which are individual objectives of the character. These could be as simple as getting on a train. The next step is to determine the character’s motivation for this action, as this in turn helps portray the emotion that the character is experiencing while completing the objective.

In addition to this, Konstantin Stanislavski created the Magic If, which asks, “What would I do if I found myself in this (the character’s) situation?” The actor steps into the character’s shoes in a given situation and asks this simple question; the answer will help the actor understand the thoughts and feelings that they need to portray for each scene. Stanislavski came up with this method because one of the jobs of an actor is to be believable in unbelievable circumstances.23

Applying it to product design

Being able to imagine ourselves as one of our users is incredibly valuable for creating empathy and a deep understanding of what matters to the user or user group in question. Stanislavski’s Magic If in particular is a useful question for product teams to ask themselves throughout the design process in order to better understand where a user may be coming from and what they may or may not want.

One piece of advice when working with personas throughout the product life cycle is to allocate one persona to one member of the team. It then becomes that person’s role to play that persona and to ensure that the persona’s needs, concerns, motivations, and goals are being considered in what’s being designed and developed. Though this doesn’t replace the need for testing the product or service with real users, it can be an effective way to ensure that the users you’re designing for are considered throughout.

Characters in Animations

Animated movies are a great example of the personification of nonhuman “things,” whether animals, toys, or other objects. Many of us have magical, or at least fond, memories of particular animated films, that have brought these nonhuman “things” to life.

Khan Academy’s Pixar in a Box feature provides a behind-the-scenes look into how Pixar develops its animations into fully developed characters; that is, those that you can imagine in almost any situation.

The lessons cover the following topics:

External versus internal features

External features are the character “design” (their clothes, what they look like), whereas inner features are their beliefs and preferences.

Wants versus needs

Wants and needs can be in conflict with each other. The wants are often what we say that we want, whereas the needs are sometimes the things we don’t realize or don’t like to admit we need. For example, in Toy Story, Woody wants to be Andy’s favorite toy, but what he needs is to learn how to share and not always be the best. In terms of their role in the story, wants often provide the entertainment, whereas the story’s emotional heart lies in the need.

Obstacles

These stand in the way of wants and needs and can be anything, including something internal like fear.

Character arc

This is how the character changes as a result of the choices they make, based on the obstacles they come across, in their quest for what they need.

Stakes

These are the things that add drama and that, together with obstacles, can often spark subplots. However, stakes can be divided into three categories:

- Internal stakes—What’s going on emotionally or mentally

- External stakes—What’s going on in the world

- Philosophical stakes—What is impacting the world, what is making the values and the belief system of this world change (or not change), and what happens then24

Applying it to product design

Wants and needs hold a lot of relevance in design. Often users think that they want something in particular when, in fact, what they need is slightly different. By making the distinction between wants and needs, we’re able to go one level deeper and separate out what users often say they want from their underlying need, and hence, identify the real value that our product and services (can) offer.

External features are usually not something we need to consider in persona development, as it doesn’t matter if we have an exact shared mental picture in our head of what our target audience actually looks like. But when we do need to consider external features when designing other characters and actors that have a role in the experience. One such example is in developing avatars for bots. What might appeal to some users will feel alienating to others, and getting the balance right, as well as allowing the user to potentially choose from a range of avatars, can help ensure that the product or service resonates with specific users. Just think of the growing number of emojis that we now have.

Just as in games, which we’ll touch on shortly, users want to be able to identify with the personification of the bot avatar. This want to identify has to do with trust and overall perception of what they’re experiencing, and as an extension of that, the brand.

Characters in Games

In some games, the avatars of the characters are predefined. In others, choosing or designing your own avatar based on predefined elements is part of the game. Gabriel Valdivia, a designer at Canopy, writes that one of the best avatar-creating flows puts the process of actually creating your avatar into the storyline. Creating the character this way is an opportunity to showcase the tone of the game and help inform the decisions the players make as they create their avatar. In Grand Theft Auto Online, for example, avatars are posing to get their mugshots taken which, as Valdivia writes, is “a cheeky way of introducing players to the sensibilities of the game.”25

Applying it to product design

A key difference between “normal” product design and game design is that for games, the player has almost always chosen to play the game. This is unlike the users of the products and services that we work on. This active choice means that the game designer needs to truly understand the player and what will get them engaged. We’ll talk more about what we can learn from player personas in the last part of this book.

Building out a detailed picture of who our personas are is not far from how the characters in adventure games are shown. We know exactly what tools or weapons they have at their disposal, and what their energy levels are at any point. Throughout their quest, our game personas will engage in fights and activities that deplete their energy levels. If they get hurt, their energy decreases even more, but when they come across the good stuff, their energy levels get recharged.

This similar to what our users are experiencing in their adventures of the products and services we design. As we talked about in Chapter 5, throughout the life cycle and the stages of the experiences we’re creating, there are bound to be barriers, whether they’re mental ones related to what the user doesn’t like doing or physical ones like forms that have to be filled in, or a choice that needs to be made. To help us narrate and plan out an experience and a storyline that resonates with our specific users, we need to know their likes and dislikes, and the kinds of encounters that will give or take energy from them.

Much more can be said about what traditional storytelling can teach us about characters than the material covered here, but that is beyond the scope of this book. Next we’ll take a look at methods and tools used in traditional storytelling in relation to characters that can benefit the product design process. Before doing so, however, we’ll explain the difference between character definition, character development, and character growth.

Character Definition Versus Character Development Versus Character Growth

There is a bit of ambiguity in each of these terms. Both “definition” and “development” possibly evolved around defining and working on who the character really is, whereas both “development” and “growth” possibly refer to how the character actually develops and grows throughout the story. For the purpose of clarity, in this book we’re using the following definitions:

Character definition

The process of identifying, and at a high level defining, the characters and actors

Character development

The process of creating believable characters by giving them depth and personality

Character growth

The process of defining how the character develops and grows throughout the story

Tools for Character Definition and Development in Product Design

Most of us are fairly comfortable with the process of identifying and, at a high level, defining who all the main users of our product or service actually are, but we rarely look beyond these users to the other characters and actors that play a smaller part. Similarly, we’re used to developing personas or proto personas for our users, but with the rise of conversational UIs, we need to start developing personas for bots and voice assistants, too. What we do less often is to look wider and define and develop more than the main user personas to include other characters and actors. And we very rarely look at how our personas, and other characters and actors, develop and grow throughout the product experience story, or what their relationships are and how these affect the product experience.

The grouping that we covered earlier in this chapter of the various characters and actors in product design is a good starting point when it comes to thinking through who plays a role and the kind of role they may play. In many instances, there is no need to define these characters and actors further than simply being aware of them, or by mapping them to when they play a part in the experience; for example, as part of a customer experience map that looks at the whole end to end experience across touch points and channels. That’s often the case with “other users,” “friends, family, partners, colleagues,” and “touch points and drivers.” The system, the brand, bots and VUIs, AI, and the antagonist may need more defining, depending on the type of product or service. The key here is that it should help define the product experience and what’s needed when and where.

Next we’ll take a look at three methods and tools from traditional storytelling and how they can help us with character definition, character development, and character growth.

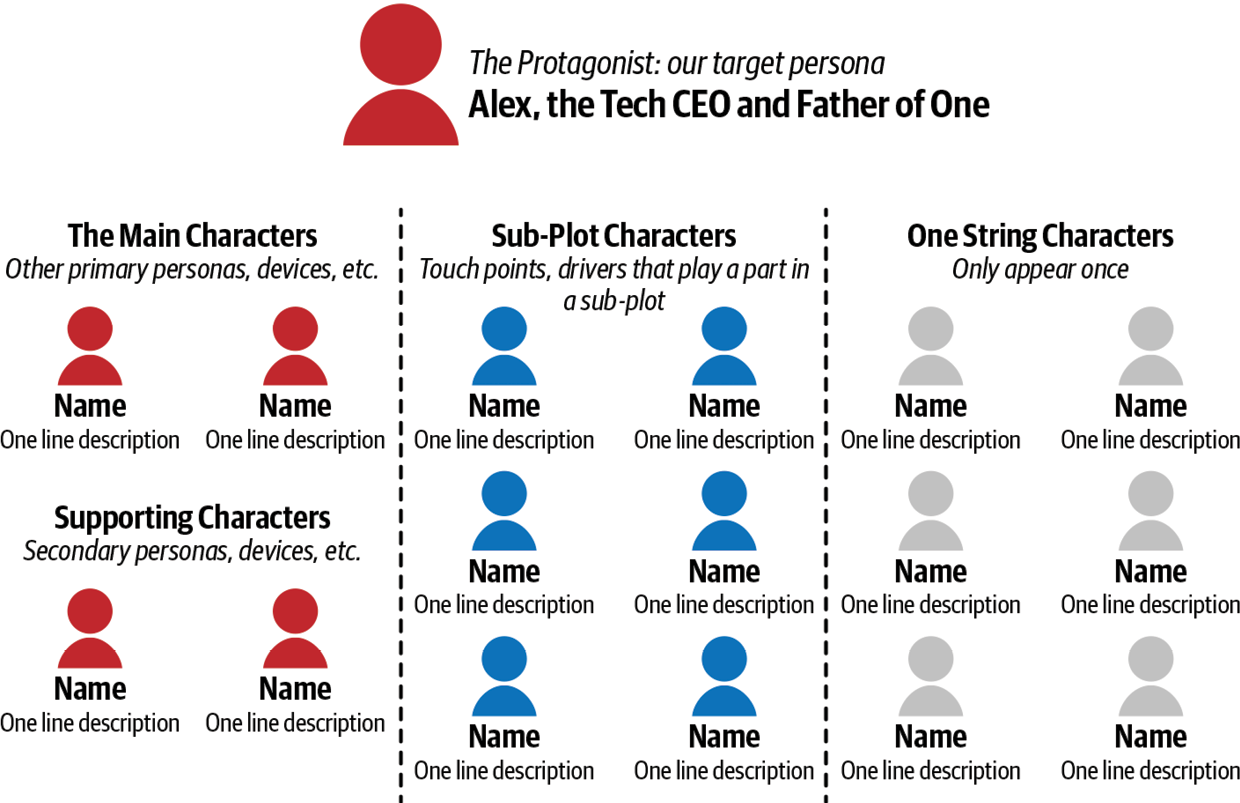

Character Hierarchy for Clarifying Role and Importance

In screenwriting, a character hierarchy indicates how characters rank in relation to other characters in terms of their importance for the screenplay (Figure 6-15). The most important one is your protagonist, as it’s their story, and without that character, there really is no story. But then you have the villains, friends, rivals, and mentors, all of which can be divided as follows:

- Main characters

- Supporting characters

- Subplot characters

- One-string characters

Who follows whom in the hierarchy will depend on the variables of the specific story. However, just as certain types of stories tend to have a certain shape (as author Kurt Vonnegut and others have defined), there are typical patterns of character hierarchy based on the type of story it is. In disaster movies, for example, friends, mentors, and rivals rank closely behind the protagonist; and in slasher movies, the rule tends to be that the longer a character survives, the more important they are. The Script Lab references that in some movies, the villain ranks nearly as high as the protagonist; Hannibal Lecter in The Silence of the Lambs is one example of a clear supporting character. Other times, the villain is actually the protagonist and becomes an anti-hero. A prime example of this is Alex in A Clockwork Orange. In buddy pictures like Lethal Weapon, Riggs and Murtaugh are partners, both with clear character arcs, but Rigg’s story is the obvious one that we follow through the film.26

Working through a character hierarchy is a useful high-level exercise to go through in conjunction with the defined plot of the product experience. It helps you think of who really matters when and why, and often results in realizations that a certain part of the experiment needs more focus to match with its importance, from, for example, the role of other users early on in the product life cycle to help drive awareness and build trust, to how the antagonist shouldn’t be forgotten. By using a simple character map sheet like the one in Figure 6-15, you get an overview of just how many characters and actors are part of the product experience and, as with many things, going through the experience will help you think of more characters.

Figure 6-15

Sample character hierarchy map

Character Questionnaires for Character Development

One of the best ways to get to know your characters is to ask a lot of questions about them. One of the tools that writers use to develop their characters is a character questionnaire, or character development questions (Figure 6-16). This list of questions is designed to make sure the characters in the story don’t become flat, but are memorable, as well as making sure the changes they go through are linked to the broader story arc. Many writers complete these questionnaires before they start to write the story, as the more you know about your characters, the richer they’ll be and, at times, the more the story will come to you.27

Figure 6-16

Sample character questionnaire from Gotham Writers (https://oreil.ly/uC7_U)

Several character questionnaires are available for download online. Some are more in depth, and others are more abstract. Many also break up the questions into sections such as:

- Basics about the character (name, hair color, their friends, and family)

- Personality (good and bad habits, strongest and weakest character trait, catchphrases)

- Past and future (ambitions, greatest achievements, strongest childhood memory)

- Daily life (eating habits, what their home is like, what they do first thing on a weekday morning respectively weekend morning, drink of choice etc.)

Editor Chuck Sambuchino writes of nine ingredients for character development for novels:28

Communication style

How does your character talk?

History

Where does your character come from?

Appearance

What do they look like?

Relationships

What kind of friends and family do they have?

Ambition

What is their passion in life? What goal are they trying to accomplish through your story? What is their unrecognized, internal need and how will they meet it?

Character defect

What’s their personality trait that irritates their friends or family?

Thoughts

What kind of internal dialogue does your character have? How do theye think through their problems and dilemmas? Is their internal voice the same as their external?

Everyman-ness

How relatable is your character?

Restrictions

More than a personality flaw, what physical or mental weakness must your character overcome through their arc?

Quite a few overlaps exist between these steps and the way we define personas. However, Sambuchino’s ingredients can add a few nuances to the character development of personas for multidevice projects. History is a good one that we often don’t do enough with in our personas—describing their backstory, their prior key experiences, and what got them here today.

Restrictions are also relevant for helping us think through how to make the individual users of the experiences we design into the hero of the story. As the “hero’s journey” outlines, the protagonist will come across help along the way in the form of a mentor or a co-hero. While we shouldn’t aim to make ourselves the co-hero in the experiences we design, or an actual mentor, we can offer help through the content and features of what we design, as well as how we design them. But in order to do that, we need to know what kind of help the users need.

How to go about it

For product design, just as for character development in storytelling, it’s about identifying what questions that will help develop the persona. We’re used to working with persona groups, demographics, tasks and goals, barriers, and more, but beyond that, using character questionnaires in product design is about what will help bring light to a persona in relation to the full end-to-end experience.

Just as traditional storytelling tends to group different questions, a good starting point is to do the same in product design.

Questions to Help Develop the Character Arc

As we’ve talked about earlier in this chapter, a character arc maps the evolution of the character’s personality over the course of the story. Depending on the type of story, the character arc can either be positive or negative.

In a positive character arc, such as that of the hero’s journey, the protagonist overcomes external obstacles and internal flaws and ends up a better person for it. At its core, this arc is made up of three points:29

The goal

The main goal that the character has in the story; it may be to fall in love or to become rich. No matter what the goal is, their journey will be hindered by it. Using Bilbo Baggins in The Hobbit for reference, his goal is to help the dwarves retrieve the treasure that was stolen and guarded by Smaug.

The lie

The lie is a deeply rooted misconception that the character has about themselves or about their world, and this misconception keeps them from reaching their true potential. To reach their goal, they need to overcome or acknowledge this lie and face the truth. Bilbo’s lie is a belief that hobbits belong in the Shire, where they are surrounded by their comforts, and that the outside world is dangerous and for braver men who can fight with a sword and take on goblins.

The truth

The truth is related to the positive change arc’s goal itself, which is self-improvement. This self-improvement is achieved when the character learns to reject the lie and embrace the truth. Bilbo’s truth is the heroic qualities that he possessed heroic qualities all along and that heroism is as much about the inner strength to follow your own moral compass when faced with adversity as it is about facing dangers.

This has some resemblance to Pixar’s wants versus needs, although in product design, an antagonist usually isn’t deliberately designed into the product experience narrative to focused on ruining things for the protagonist. However, as we’ve covered, the antagonist can be internal too, and just as Pixar explains, what users think they want is often slightly different from what they actually need.

How to go about it

Working through the goal, the lie, and the truth for each of your main personas is a quick and easy exercise to help identify what it is that they are overcoming, be that external obstacles or barriers, or internal ones.

You may do this by just sitting down and discussing or thinking through what each of these may be. Another way to approach this is to do it in relation to your product experience narrative.

Summary

Though there are different ways to come up with a story, all stories are better with a focus on characters. Similarly, all products are better when we focus on the users that we’re building them for, and when we are clear on all the other actors that play a part in that product experience. Starting to define the personas of your characters and actors is the first step in understanding what will matter in the experience. To get a more complete picture that helps identify the bigger picture as well as the details throughout the different points in their journey, we need to go one step deeper, and that is really where the fun begins.

What’s common in both the design and the storytelling world is that we have to do research into the characters of the stories we’re telling, and into the users of the products and services that we’re designing for. We must know our characters/users inside out not just to be able to tell a good story, but to ensure we know all the whys. Why does the character want to be in the story? Why does the user want to use your product and service?

As this chapter has covered, there’s more than what immediately meets the eye when it comes to characters and actors in the products and services that we define. The more complex these become, the more important it is that we’ve defined who plays a role, when, and where, so that we can ensure that the experience flows. By considering and accounting for all aspects that should be defined, we can ensure the most optimal outcome for users and the business.

Character development is something that we very rarely get involved with in product design. However, significant benefits could be reaped if we continuously spend time throughout the product design process on character development of our personas.

It’s the characters of a story that we invest in emotionally. We want to know what happens to them. Whether we root for the good or the bad guy, we develop empathy for them through the challenges they face, the weaknesses they overcome, and, of course, through their quest to reach or achieve their goal. We want to know what happens and how the story is going to end, and in most cases, we want things to go well for them.